In Touch With the Galaxy

The art and genius of Lorna Simpson.

The Art and Genius of Lorna Simpson

A new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art tracks what has changed and what has remained the same in the artist’s work.

Lorna Simpson’s work unfolds slowly. Throughout a career that has spanned nearly four decades and encompasses photography, conceptual practices, collage, sculpture, and now painting, Simpson has created works of art that resist quick and easy reads. Instead, she requires us to reconsider our readiness to assign a secure interpretation to what we see. In her work, past and present, Simpson walks us through the dominant codes of meaning, then takes us beyond them to encounter the singular, the private, and the utterly individual.

A new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Lorna Simpson: Source Notes,” presents a group of paintings and related works created by Simpson during the past decade—and offers an opportunity to reflect on the conceptual practice she developed during the 1980s and ’90s. While Simpson’s earlier work asked viewers to draw connections between the photographs, text placards, and objects she staged in carefully composed ensembles, the paintings on view at the Met offer single images, monumental and silent: a meteorite hovering in space, an Arctic landscape locked in ice, a woman’s face and body breaking forth from a crashing waterfall. These newer works lend themselves to meaning perhaps even more hesitantly than Simpson’s early work did. Although they offer little in the way of immediate insight, there are significant rewards for those who are willing to take the time.

A former documentary photographer, Simpson harnessed the medium in her early practice to develop a body of work that explores how meaning is assigned to the body and its images. Her ensembles from this period link cryptic snatches of text with crisp and composed photographs of individuals, usually Black women. Yet although she made photography central to her practice, Simpson subverted the medium’s traditional aims. Photography is celebrated for its unique capacity to render individual personhood indisputable. By their nature, photographs insist that their subjects were present at the making of the image (although AI has since changed that). While the documentary and street photography of the 1970s—the milieu into which Simpson entered as a photographer—doubled down on the medium’s capacity to capture and preserve the candid singularity of everyday existence, Simpson ultimately went in the opposite direction: Her early work challenges both the claims that photography makes to truth and the supposed power of photographic images to render their subjects knowable to viewers.

Simpson’s photographs from this period stage their subjects against blank grounds. Almost universally, these women are clothed in a plain white shift dress, a nondescript but evocative garment—a modern nightgown that somehow also smacks of the 19th century, of the plain and shapeless clothing of the enslaved. The women are seen from behind or cropped at the neck, so that their faces—that privileged locus of personhood in the Western image-making tradition—never appear. Instead, as we seek to understand these images, we are forced to turn to the language that Simpson has appended to them. These cryptic texts are not captions; they do not narrate the image or reinforce its claim to truth. Instead, they conjure dominant codes of meaning and frameworks for knowing only to demonstrate their dubious applicability. They ask, in the end, whether we can make any claims to knowledge at all.

In You’re Fine, an ensemble from 1988, we see a woman lying on her side, her back to the viewer. She is bracketed, left and right, by text engraved on gold plastic plaques and, top and bottom, by text composed of ceramic letterforms. On the left, there’s a list of the body parts and bodily functions assessed during a physical exam: “heart,” “reflexes,” “abdomen,” “urine,” “height,” “weight.” On the right, there’s the hoped-for outcome dependent on the data gained from these tests: “Secretarial Position.” Above and below appear the twinned statements “You’re Fine” and “You’re Hired.”

The work is based on Simpson’s experience of undergoing a medical exam as a condition of employment. Suspended within a grid of meaning, the Black female body in this ensemble is transformed first into a suite of medical data and then into an employee, an experience of depersonalization that is both particular and universal. In this photograph, Simpson reworks the odalisque, the reclining female nude of 19th-century European art, yet deflects the erotic gaze to suggest different forms of penetration, instead framing the Black woman as the subject of medical probing. Beneath this ensemble’s surface of intelligibility, histories of racialized medical violence lie concealed—the unanesthetized tests on enslaved women that provided a foundation for modern gynecology, for example. By staging her subject in a pose that suggests, but ultimately evades, the aesthetic of female sexual availability, Simpson points to other forms of exploitation. This female subject, fitted with a clean bill of health, may sell her labor on the free market—but what conditions met the Black woman professional who took up a “Secretarial Position” in the 1980s? What was her experience, both of the medical examination and of employment? Simpson’s strategy is to leave such questions open, forcing viewers to arrive at the answers themselves.

If, in You’re Fine, Simpson stages the individual within a broad grid of intelligibility, in another work, 1989’s Dividing Lines, she reveals the leaps we take to arrive at meaning. Confronted by a photograph and its seeming caption, we expect language and image to elucidate one another, to form a cohesive and legible whole. Yet which of the fragments of text in Dividing Lines should we bring to bear on Simpson’s side-by-side and seen-from-behind photographs of a Black woman with short, braided hair? Plastic plaques, engraved with red words, offer us associative play on the term line: “Out of line,” “Silver lining,” “Same ol’ line,” “Color line.” Is the Black female figure before us the subject of “red lining” or a suspect in a “line-up”? Or is this the “same ol’ line,” the allegation of racism? Why does it take an act of cognitive will to associate her with the phrases “line one’s pockets” and “actor’s lines”? The duplication of the figure and the subtle differences between the two images further confound attempts to establish a secure meaning. There are subtle but unmissable differences—the muscles of the figure on the right are visibly tensed, as if the subject has squared her shoulders or even more resolutely turned her back to the viewer, rejecting each and every attempt to read the text of her body.

In You’re Fine and Dividing Lines, Simpson’s language invokes authority, testing its own power to prescribe a reading of the depicted bodies. Elsewhere, however, her text is strangely candid, cryptic only in the way of overheard fragments of conversation. In 1991’s Myths, Simpson presents us with three images of what seem to be African masks, seen from the inside, as if we ourselves were about to don them. These appear alongside another image of a Black woman with her back turned to us. The ensemble is unsettling in its total facelessness, yet the accompanying text is strangely quotidian. One of the six engraved plaques reads: “said that Stevie Wonder wrote My Cheri Amour for her older sister.” Others: “they said they were related to them/they had the same name” and “swore that those were the same sling-backs worn by Dorothy Dandridge in Carmen Jones.”

If the three masks evoke identities one might take up or put on, these stray fragments of text suggest attempts to cohere a sense of personal identity out of disparate references and experiences. This weaving of lies or partial truths into the fabric of the self feels familiar to me, reminds me of how I once told my middle-school classmates that Barack Obama was a distant cousin. It’s a broadly shared experience, yet Simpson carves out space for its particular expression here: Only some people (Black people) can persuasively claim that Stevie Wonder wrote a song for their older sister, or that they are related to the first Black president. As she does elsewhere, Simpson here bridges the particular and the universal, exploring the human experience of self-fashioning by inhabiting the specific space of a selfhood constructed out of the signifiers of Black American identity.

Raised in New York City, Simpson studied at the School of Visual Arts and then at the University of California, San Diego, whose MFA program she graduated from in 1985. Her work was immediately recognized as significant. Following her first solo show at Just Above Midtown, or JAM, a gallery dedicated to showing the work of contemporary Black artists, Simpson became, in 1990, the first Black woman artist to be featured in a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art.

Simpson’s photography-based conceptual art shares strategies with the work of the artists who came to be known as the Pictures Generation. From the 1970s to the early ’90s, members of this loosely affiliated group investigated the construction and fragmentation of gender and class identities in the moment of mass media. Barbara Kruger’s aphorisms, Cindy Sherman’s restagings, and Sherrie Levine’s postmodern questioning of photographic authority and authorship open onto similar territory as Simpson’s explorations.

Simpson’s work did not appear in the major Pictures Generations exhibitions; nor is it engaged alongside the work of these artists today, perhaps because, then and now, the work of Black artists is often seen to form a distinct category. The difference in the critical reception of Simpson’s work and that of the artists of the Pictures Generation makes clear the distinct expectations for “Black” art. While artists like Kruger and Richard Prince were celebrated for their detachment, for the cool and critical distance they maintained from their subject matter, critics wondered why Simpson—a Black artist ostensibly making work about racial injustice (for what else could it possibly be about?)—was not more angry.

In the years since she debuted her breakthrough photography-and-text ensembles, Simpson has continued to explore representation, meaning, and the ways that language informs our understanding of images. Her practice is wide-ranging: She works with film and video and draws on techniques that include printmaking and collage. In 2014, she also started painting. Her solo exhibition at the Met shares with us this most recent decade of her practice.

The immediate sensation, upon stepping into the exhibition’s single gallery, is of being drenched in cool ultramarine. The watery hue saturates most of the works on view, which feel touched or worked in ways that Simpson’s almost clinical photographic ensembles do not. These paintings are massive—and silent. The textual strategies that characterize Simpson’s earliest work have been set aside for the time being. Instead, the paintings rely on found photography, the “source notes” of the exhibition’s title, reworked into monumental painted compositions.

Around 2010, Simpson started to assemble an archive of images, mostly gathered from Ebony and Jet. Established in the mid–20th century, the magazines, in the words of their founder, “dealt with the whole spectrum of black life,” from politics and culture to fashion and celebrity. Simpson began by working clippings from these magazines into small-scale collages, several of which accompany her large-format paintings in the Met exhibition. In most of these collages, Simpson relies on a single, striking transposition. In one, a barefoot Black man strides forward into a flurry of snowflakes, magnified to a massive scale. In another, a reworking of a photograph published in Jet, the face of a woman wearing a cheetah print is swapped with that of her leashed pet cheetah. This tiny and surreal collaged image is reprised on a grand scale in one of the show’s paintings, in which Simpson, re-creating her own collage in brushy strokes of black paint, homogenizes her cut-and-pasted referent into a single incredible image.

Jet was famed for its “Beauty of the Week” feature, which displayed a self-submitted photograph of a Black woman in each issue. These women—aspiring models, waitresses, college students, paralegals—appeared accompanied by a few lines about their interests and hometowns. It was perhaps from these pages that Simpson pulled the cat-eyed and carefully coiffed figures that gaze out from many of the paintings in the show. Extracted from magazines, these anonymous women have been scaled up, reproduced in dot-matrix tonality, and screen-printed onto fiberglass panels. Simpson has merged photographs of individual women, blending and layering their features to create composite portraits. Ink, brushed on in broad swathes, both enhances and obscures their features. The effect is a little uncanny: What at first seems a unitary portrait of a single individual is revealed as an amalgam.

Although their faces are turned toward us, the anonymous women that appear in Simpson’s recent paintings are as opaque as the subjects of her earlier work. Any writing that might have informed us of their identity lies sealed within decades-old magazines. The exhibition’s sole sculptural work drives this point home: Piled atop a stool, with what appears to be a block of ice beneath it, a stack of Jet and Ebony magazines, many encased in plastic sleeves, are surmounted by a peeling bust of a Black woman with braided hair. The sculpture is one in a series of similar stacks that Simpson began creating in 2017. They stand as monuments to an expression of Black culture rendered defunct by the end of Jet’s and Ebony’s publication in print and the bankruptcy of their parent enterprise, the Johnson Publishing Company. By erecting these monuments and rendering her source material unreadable, Simpson seems to de-mediate and untether the women that formerly populated the pages of these Black periodicals, leaving us simply with the fact of human presence.

The unmelting ice that rests beneath Simpson’s sculpture is echoed in another group of paintings. We gaze out across vast landscapes of glaciers, ice floes, and snowy mountains. These images have been constructed from vintage photographs of the Arctic. Scaled up and screen-printed, they have been reworked with ink overlays that in some places reveal the artist’s hand and her energetic brushwork, and in other places the random contingency of the dripping and spattered medium. Simpson has linked these paintings and their seemingly endless vistas to the Black navigator and explorer Matthew Henson. The child of sharecroppers, Henson accompanied Robert Peary on seven voyages to the Arctic, including the expedition in 1909 that Peary claimed was the first to reach the North Pole (though later calculations revealed that the party may have been some 30 miles short of the destination).

What did it mean to turn a Black gaze upon the Arctic? In these works, Simpson is thinking with Robin Coste Lewis, who in her poem “Using Black to Paint Light: Walking Through a Matisse Exhibit Thinking About the Arctic and Matthew Henson” writes:

The unanticipated shock: so much believed to be white is actually—strikingly—blue. Endless blueness. White is blue. An ocean wave freezes in place. Blue. Whole glaciers, large as Ohio, floating masses of static water. All of them pale frosted azuls. It makes me wonder—yet again—was there ever such a thing as whiteness? I am beginning to grow suspicious. An open window.

Henson himself reflected on the conjunction of identity and place in his 1912 memoir, A Negro Explorer at the North Pole. Simpson invites us to look through Henson’s eyes into a vast silence. Slivers of illegible text—babbling columns of letters—rise out of the ice like signal flares or pins plunged into a map, suggesting both speechlessness and the effort to fix the landscape, or its memory, in language.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Speechlessness, or language’s inadequacy, is also suggested by one of the show’s smaller and most intriguing paintings. Within a border formed by a screen-printed magazine page evacuated of all content, a set of abstract marks suggest faded or rain-washed writing. These stranded serifs and ligatures, commas and quotation marks, veer so close to legibility that to not be able to read them is genuinely frustrating. Smaller script at the bottom tells us that the screen-printed surface began its life as the 16th page of an issue of Ebony magazine from April 1979, then notes that its content may be further perused on page 18. In Simpson’s earlier work, photographed figures were seen from behind. Now, text and writing itself have turned their back to us.

In Simpson’s earlier work, text established a range of inquiry, providing an open-ended framework for engagement. In these new paintings, silence safeguards their inscrutability. Some messages might get lost. You could drown in these works, in the pleasures of scale and hue, in the grandeur of the Black female figure, without critical reflection. There is freedom here: Simpson’s freedom to experiment with image and medium, the viewer’s freedom to associate freely—although I myself miss the gridded networks of meaning that structure other areas of Simpson’s practice.

Simpson has long spoken of her desire to make works of art that deploy the Black figure as a universal subject—and of her frustration with critical viewpoints that block such readings. While the work of other artists “is interpreted as speaking universally about the body,” she once noted, “when I do it I am speaking about the black body.” Simpson’s paintings about Matthew Henson and the Arctic explore this territory. By establishing Henson, a Black man, as a point of identification for viewers gazing into the icy vastness of these paintings, Simpson invites us into the universal experience of the sublime—but holds fast to the particularities of Black experience. It’s as though the figure looking out across the abyss in Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (also recently on view at the Met), who stands as the proxy for the viewer’s experience of transcendental distance and depth, were a Black woman.

Other paintings in the exhibition also bring Black figures into contact with the expansive, the vast, and the sublime. Two of the exhibition’s most towering works merge the bodies of Black women with a crashing waterfall and the rocky earth. Another enormous painting, the monumental did time elapse, shows a chunk of rock hovering in the composition’s center. It is a meteorite, eternally halted in its course. The work reflects Simpson’s musing on a historical episode that she came across in a vintage science textbook: In 1922, a Black sharecropper named Ed Bush (though his name did not appear in the text) saw a meteorite strike earth mere feet from where he was standing, on Mississippi farmland owned by a white judge and landlord named Allen Cox. From his particular position within American post-slavery labor regimes, Bush briefly came to share coordinates with a conglomeration of rock and metal shot out of endless space. Silently, this single massive image unites the tenant farmer’s plot with the galaxy, his personal experience with vaster orders of time and space. It is Simpson’s talent, honed across decades, to show the particular and the universal at once, to those willing to take the time to see it.

Take a stand against Trump and support The Nation!

In this moment of crisis, we need a unified, progressive opposition to Donald Trump.

We’re starting to see one take shape in the streets and at ballot boxes across the country: from New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani’s campaign focused on affordability, to communities protecting their neighbors from ICE, to the senators opposing arms shipments to Israel.

The Democratic Party has an urgent choice to make: Will it embrace a politics that is principled and popular, or will it continue to insist on losing elections with the out-of-touch elites and consultants that got us here?

At The Nation, we know which side we’re on. Every day, we make the case for a more democratic and equal world by championing progressive leaders, lifting up movements fighting for justice, and exposing the oligarchs and corporations profiting at the expense of us all. Our independent journalism informs and empowers progressives across the country and helps bring this politics to new readers ready to join the fight.

We need your help to continue this work. Will you donate to support The Nation’s independent journalism? Every contribution goes to our award-winning reporting, analysis, and commentary.

Thank you for helping us take on Trump and build the just society we know is possible.

Sincerely,

Bhaskar Sunkara

President, The Nation

More from The Nation

The Empty Provocations of “Eddington” The Empty Provocations of “Eddington”

Ari Aster’s farcical western is billed as a send-up of the puerile politics of the Covid years. In reality, it’s a film that seems to have no politics at all.

The Rot at Fort Bragg The Rot at Fort Bragg

Seth Harp exposes how all the death and crime surrounding one military base is not an aberration but representative of the fratricidal impulse of the armed forces at large.

The Revolutionary Politics of “Andor” The Revolutionary Politics of “Andor”

The latest addition to the "Star Wars "series offers an intricate tale of radicalization and its costs.

Billy Wilder’s Battle With the Past Billy Wilder’s Battle With the Past

How the fabled Hollywood director confronted survivor’s guilt, the legacies of the Holocaust, and the paradoxes of Zionism.

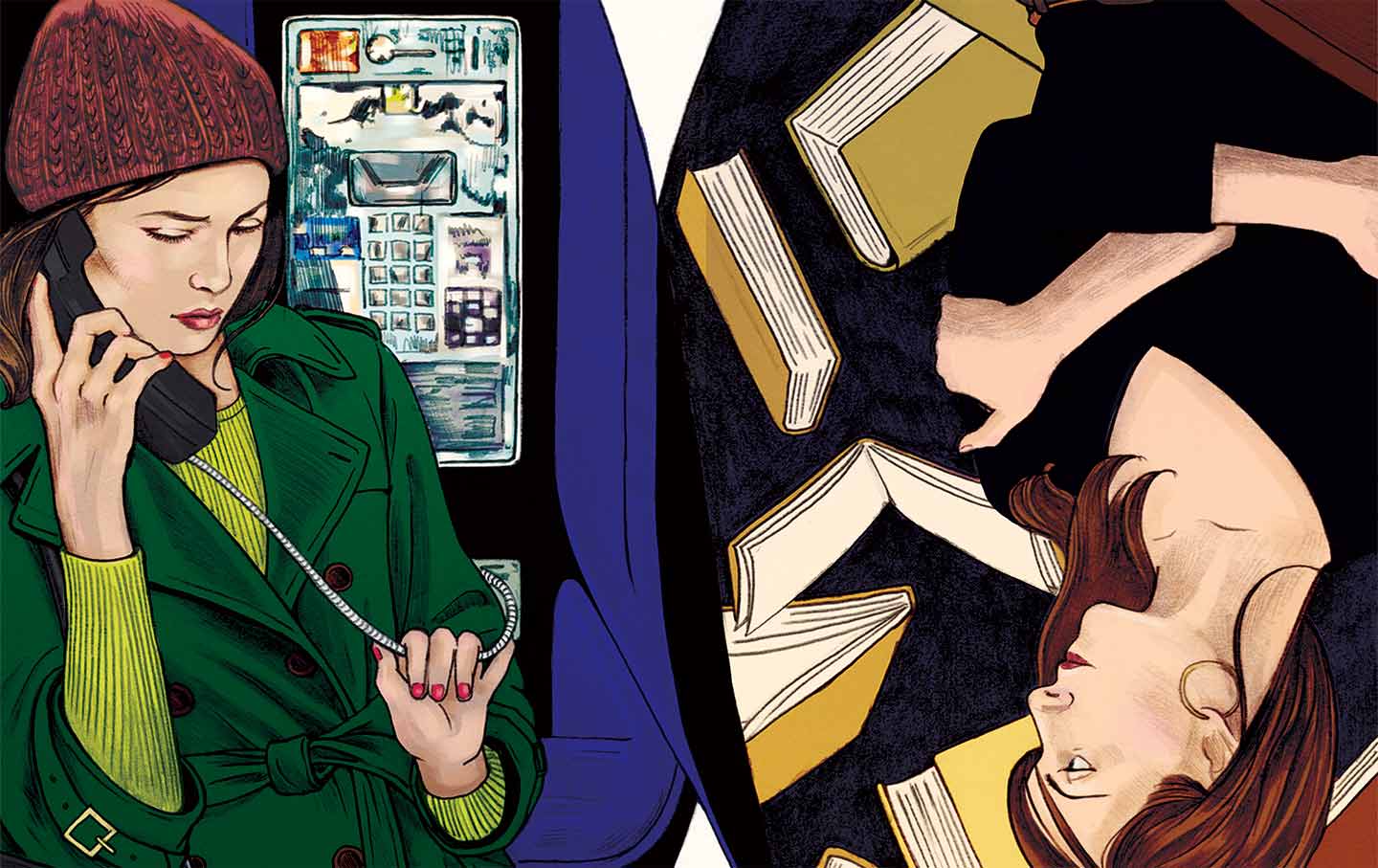

Catherine Lacey’s Missed Connections Catherine Lacey’s Missed Connections

In her most personal work, "The Möbius Book", Lacey uses a devastating moment of heartbreak to ruminate on the messy intersections between life and writing.