Trump’s Regime Change Fantasy Involves Bringing Back the Shah

The United States and its allies are toying with liberating Iran with the help of some unsavory friends.

Mainly exiles and German-Iranians protest against the mullah regime in Iran at a rally in Frankfurt, Germany. One man holds a photo of Reza Pahlavi II, who is living in exile.

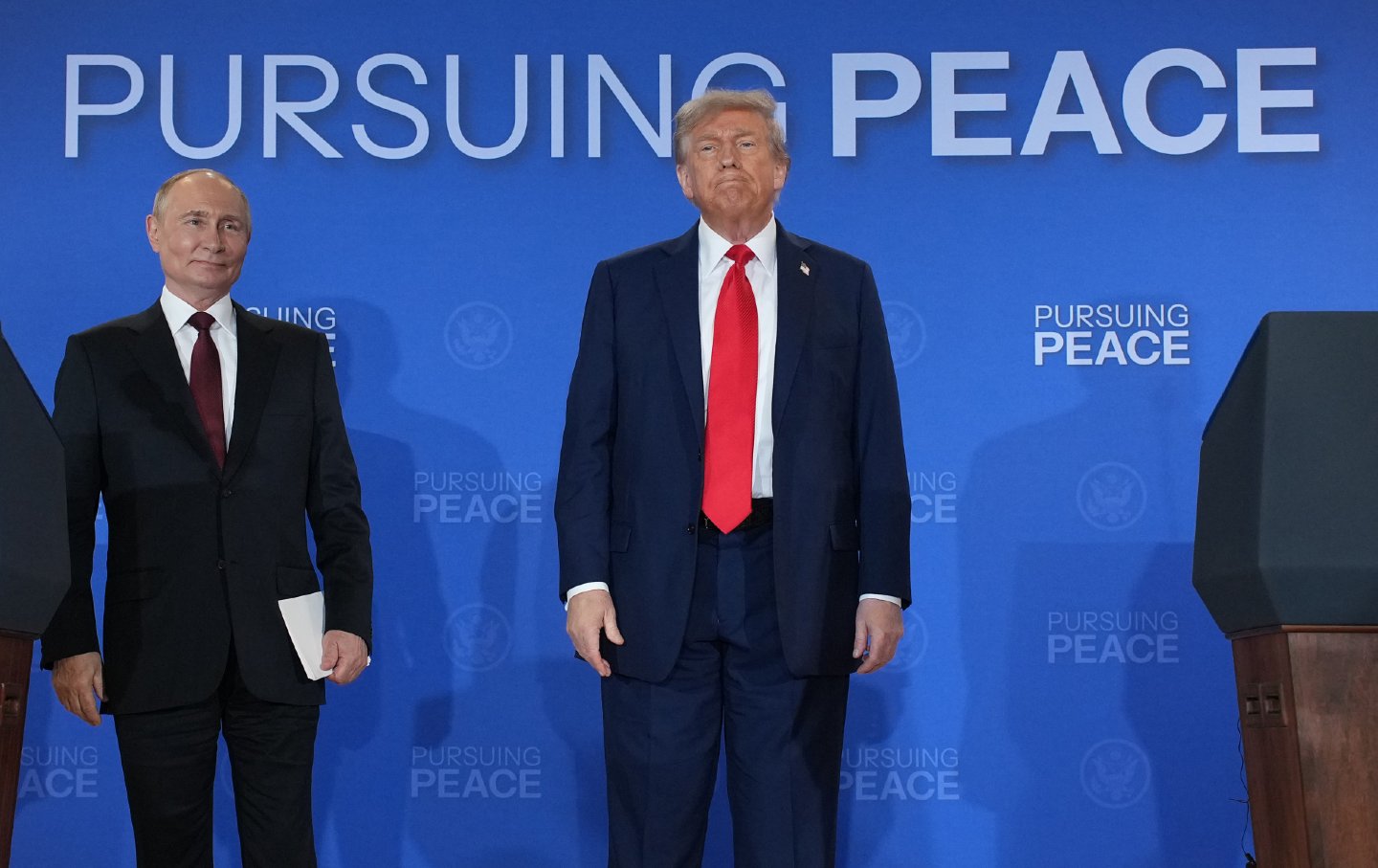

(Boris Roessler / picture alliance via Getty Images)Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was born to inherit a throne, groomed to govern a nation, but ended up spending almost his entire adult life as a pretender, a would-be monarch in exile nursing ambitions of restoration. Pahlavi’s fate might be pitiful if his political goals were not so obscene. For more than a century, his family has been in the thick of imperialist intrigue and coup attempts that have worked to deprive his native land of democracy and human rights. Pahlavi’s current plots to make him Iran’s ruler have brought him into alliance with an unsavory crew of authoritarians headed by US President Donald Trump, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. It’s this alliance that raises Pahlavi from a pathetic wannabe to a threat to peace in the Middle East and the hopes for a democratic revolution in Iran.

As royal dynasties go, the Pahlavis are parvenus. The founding father, Reza Shah Pahlavi (1878–1944), was a military officer who hijacked a democratic movement to tame the absolutist Qagar dynasty and turn the country into a constitutional republic. The Pahlavi patriarch extinguished this dream in 1925 by consolidating centralized power as the newly crowned shah. He was forced to abdicate in 1941 when his pro-German sympathies earned the ire of the Allies. His son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, took power that year.

In 1951, another movement for democratizing Iran, led by Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh, again tried to limit the power of the monarch. Mosaddegh also pushed for the nationalization of the oil industry so that profits could benefit the Iranian people. This was unacceptable to Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s imperial patrons, the United Kingdom and the United States. In 1953, Mosaddegh was overthrown in a CIA-orchestrated coup. which had the desired effect of entrenching Pahlavi rule as a compliant dictatorship. A CIA internal history of the coup, written in 1954, described the coup with a lyricism usually reserved for nostalgic reveries about romantic success: “It was a day that should never have ended. For it carried with it such a sense of excitement, of satisfaction and of jubilation that it is doubtful whether any other can come up to it.”

The giddy joy of US foreign-policy planners in 1953 turned to bitter gall in 1979, when the brutal dictatorship of the Pahlavi family was swept away in a revolution that was ultimately hijacked by Islamic theocrats. The revolution brought an end to decades of Western domination over Iran. For this reason, even Iranians who despise the rule of the ayatollahs and yearn for a more democratic regime are loath to make common cause with the Pahlavi project of monarchical restoration, which are rightly seen as tainted not just by the authoritarianism but also by a record of subservience to foreign powers.

Born in 1960, Reza Pahlavi was already living in the United States when the Iranian revolution broke out. He has not lived in Iran since 1978. Despite this liability, he has offered himself up as the savior of his country since the 1980s.

Pahlavi’s pretenses to leadership now should be taken more seriously because of Israel’s attack on Iran in June, which was greenlighted by the Trump administration. Despite Trump’s explicit rejection of regime change in Iran and his frequent disavowals of an interventionist foreign policy, in practice the president’s administration has been supporting the fantasy of a Pahlavi restoration.

Writing in the Boston Review, the anthropologist Alex Shams documents at length the institutional support Pahlavi’s restorationist project has received from both the United States and its allies in the Middle East:

The governments of Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the United States, alongside private actors, have spent millions building up Pahlavi and regime-change sentiment more broadly while promoting attacks on those who oppose him or U.S. and Israeli attacks on Iran. The propaganda effort takes two forms. First, Pahlavi’s backers have lavished funding on monarchist Persian-language TV outlets, where he appears regularly. Second, they have built a digital network of social media accounts to spread disinformation and target pro-democracy voices on social media—those Iranians, at home and abroad, who oppose the regime but also reject kings and foreign-backed coups. Pahlavi’s supporters are primarily exiles, backers of the shah or their descendants, but with the help of royalist broadcasters, D.C. think tanks, and online trolls, he has gained ground among Iranians desperate for an alternative to the Islamic Republic.

Shams convincingly distinguishes between the organic pro-democracy movements inside Iran, which have garnered strength from legitimate grievances against the Islamic Republic’s authoritarianism and misogyny, and the Pahlavi project, which has all the signs of a manufactured program of manipulation. Relying on donations from foreign governments to create a media echo chamber, the monarchist cause is a Potemkin mass movement. As Shams notes, having monarchists as the public face of the democracy movement only strengthens the hands of the Islamic republic.

One easy way to judge the good faith of the monarchists is by the quality of their sponsors. The United States, Saudi Arabia, and Israel have no credibility when it comes to democracy. The United States has supported autocracies in the region for decades, finding them much more subservient than democracies. Saudi Arabia itself is a theocratic monarchy fearful of mass movements. Israel is a Herrenvolk democracy that has repeatedly sought to shore up its position in the region by destabilizing its neighbors. Currently, it is waging a ferocious slaughter of civilians in Gaza that is bolstered by attacks on many neighboring countries (including Yemen, Lebanon, Syria, and Iran). Given the violence that the United States and its allies are already spreading in the region, the new push for regime change in Iran will only add fuel to the fire.

The Pahlavi project is far from the first case of an exile movement with limited popular support presenting itself as an agent of regime change and liberation. Shams cites the example of the Iraqi exile Ahmed Chalabi, whose fabrications aided then–President George W. Bush’s propaganda campaign for invading Iraq. A similar role was played by Cuban exiles during the Bay of Pig invasion and Chinese exiles in Taiwan who purported to represent the authentic government of mainland China.

In his classic work The History of England from the Accession of James the Second (1848), the Victorian historian Thomas Babington Macaulay had some clarifying thoughts on the illusions that exile communities are prone to. Macaulay was writing about a group of Whigs who had fled England in the reign of Charles II and plotted the ill-fated Rye House Plot of 1683 to assassinate the king and his brother. According to Macaulay:

These refugees were in general men of fiery temper and weak judgment. They were also under the influence of that peculiar illusion which seems to belong to their situation. A politician driven into banishment by a hostile faction generally sees the society which he has quitted through a false medium. Every object is distorted and discoloured by his regrets, his longings, and his resentments. Every little discontent appears to him to portend a revolution. Every riot is a rebellion. He cannot be convinced that his country does not pine for him as much as he pines for his country. He imagines that all his old associates, who still dwell at their homes and enjoy their estates, are tormented by the same feelings which make life a burden to himself. The longer his expatriation, the greater does this hallucination become.

Of course, the pattern that Macaulay describes isn’t universal. There have been plenty of exiles, ranging from Vladimir Lenin to the Ayatollah Khomeini, who have successfully plotted revolutions while living abroad. Still, Macaulay’s account rings true for a particular type of reckless adventurer: one who is detached from the experience of ordinary people and reliant on the patronage of imperial allies. The tragedy is that when backed by empire and dictatorship, the hallucinations of weak-minded men lead to assassinations and bombs.

Take a stand against Trump and support The Nation!

In this moment of crisis, we need a unified, progressive opposition to Donald Trump.

We’re starting to see one take shape in the streets and at ballot boxes across the country: from New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani’s campaign focused on affordability, to communities protecting their neighbors from ICE, to the senators opposing arms shipments to Israel.

The Democratic Party has an urgent choice to make: Will it embrace a politics that is principled and popular, or will it continue to insist on losing elections with the out-of-touch elites and consultants that got us here?

At The Nation, we know which side we’re on. Every day, we make the case for a more democratic and equal world by championing progressive leaders, lifting up movements fighting for justice, and exposing the oligarchs and corporations profiting at the expense of us all. Our independent journalism informs and empowers progressives across the country and helps bring this politics to new readers ready to join the fight.

We need your help to continue this work. Will you donate to support The Nation’s independent journalism? Every contribution goes to our award-winning reporting, analysis, and commentary.

Thank you for helping us take on Trump and build the just society we know is possible.

Sincerely,

Bhaskar Sunkara

President, The Nation